Nikolai Vavilov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

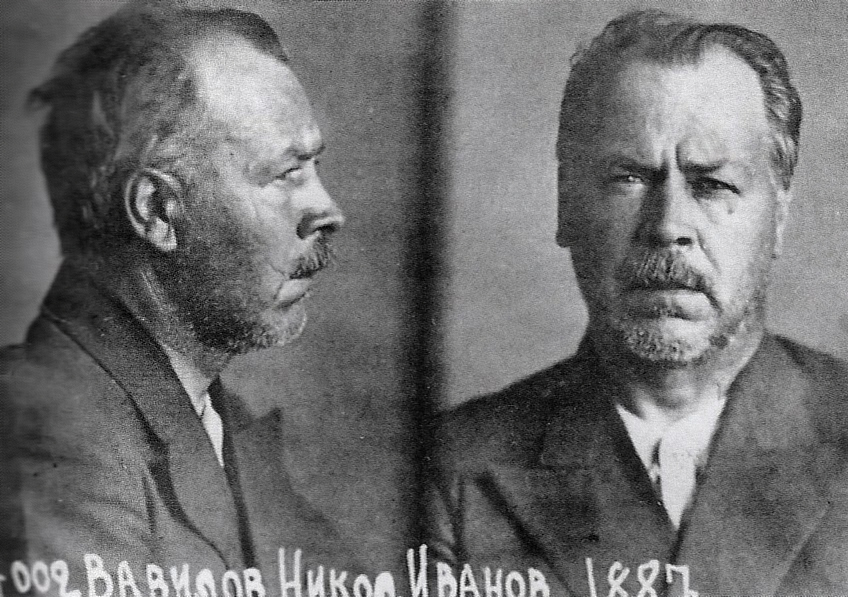

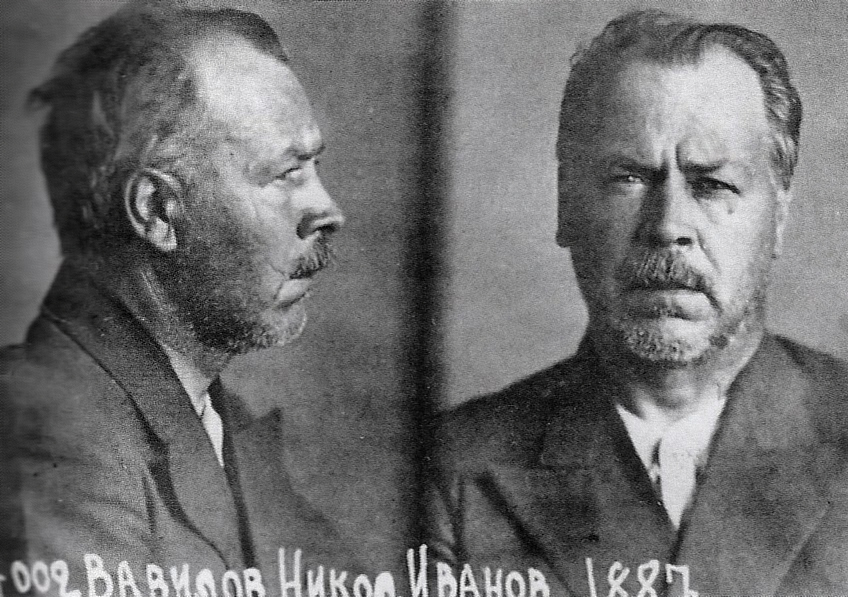

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov ( rus, Никола́й Ива́нович Вави́лов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ vɐˈvʲiləf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Ivanovich_Vavilov.ogg; – 26 January 1943) was a Russian and

Vavilov was born into a merchant family in

Vavilov was born into a merchant family in  While developing his theory on the centers of origin of cultivated plants, Vavilov organized a series of botanical-agronomic expeditions, and collected seeds from every corner of the globe. In 1927, he presented the centers of origin to the public on the Fifth International Congress of Genetics in Berlin (''V. Internationaler Kongress für Vererbungswissenschaft Berlin''). In

While developing his theory on the centers of origin of cultivated plants, Vavilov organized a series of botanical-agronomic expeditions, and collected seeds from every corner of the globe. In 1927, he presented the centers of origin to the public on the Fifth International Congress of Genetics in Berlin (''V. Internationaler Kongress für Vererbungswissenschaft Berlin''). In  Vavilov encountered the young

Vavilov encountered the young

(in Russian) Some authors assert that the actual cause of death was starvation. The Pavlovsk Experimental Station, Leningrad seedbank was preserved and protected through the 28-month long Siege of Leningrad. While the Soviets had ordered the evacuation of art from the

Земледельческий Афганистан. (1929) (''Agricultural

Земледельческий Афганистан. (1929) (''Agricultural

link

*''Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants'' (translated by

Five Continents

' (translated by

Vavilov, Centers of Origin, Spread of CropsVavilov Center for Plant IndustryGenetic Resources of Leguminous Plants in the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry

* ttps://www.marxists.org/subject/science/essays/speeches.htm#vavilov Speech at the 1939 Conference on Genetics and Selectionbr>Theoretical base of our researches

{{DEFAULTSORT:Vavilov, Nikolai Ivanovich 1887 births 1943 deaths Scientists from Moscow People from Moskovsky Uyezd All-Russian Central Executive Committee members Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members Russian atheists Russian agronomists Soviet botanists Soviet agronomists 20th-century Russian botanists Botanists with author abbreviations Russian geneticists Soviet geneticists Russian geographers Soviet geographers Russian explorers 20th-century geographers Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Members of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Academicians of the VASKhNIL Foreign Members of the Royal Society Deaths by starvation Soviet people who died in prison custody Prisoners who died in Soviet detention Soviet rehabilitations

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

agronomist

An agriculturist, agriculturalist, agrologist, or agronomist (abbreviated as agr.), is a professional in the science, practice, and management of agriculture and agribusiness. It is a regulated profession in Canada, India, the Philippines, the ...

, botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

and geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

who identified the centers of origin

A center of origin is a geographical area where a group of organisms, either domesticated or wild, first developed its distinctive properties. They are also considered centers of diversity. Centers of origin were first identified in 1924 by Ni ...

of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

and other cereal crops

A cereal is any Poaceae, grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, Cereal germ, germ, and bran. Cereal Grain, grain crops are grown in greater quantit ...

that sustain the global population.

Vavilov's work was criticized by Trofim Lysenko

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (russian: Трофим Денисович Лысенко, uk, Трохи́м Дени́сович Лисе́нко, ; 20 November 1976) was a Soviet agronomist and pseudo-scientist.''An ill-educated agronomist with hu ...

, whose anti-Mendelian

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

concepts of plant biology had won favor with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

. As a result, Vavilov was arrested and subsequently sentenced to death in July 1941. Although his sentence was commuted to twenty years' imprisonment, he died in prison in 1943. According to Lyubov Brezhneva

Lyubov Yakovlevna Brezhneva (russian: Любовь Яковлевна Брежнева) is a niece of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev (an illegitimate but acknowledged daughter of Leonid's brother, Yakov Brezhnev). She was hounded by the KGB for ma ...

, he was thrown to his death into a pit of lime in the prison yard. In 1955 his death sentence was retroactively pardoned under Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

. By the 1960s his reputation was publicly rehabilitated and he began to be hailed as a hero of Soviet science

Science and technology in the Soviet Union served as an important part of national politics, practices, and identity. From the time of Lenin until the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s, both science and technology were intimately linked ...

.

Life

Vavilov was born into a merchant family in

Vavilov was born into a merchant family in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, the older brother of physicist Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov

Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Вави́лов ( – January 25, 1951) was a Soviet physicist, the President of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union from July 1945 until his death. His elder brothe ...

. His father had grown up in poverty due to recurring crop failures and food rationing, and Vavilov became obsessed from an early age with ending famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompani ...

.

Vavilov entered the Petrovskaya Agricultural Academy (now the Russian State Agrarian University – Moscow Timiryazev Agricultural Academy

Moscow Timiryazev Agricultural Academy (full name in russian: Российский государственный аграрный университет — МСХА имени К.А. Тимирязева) is one of the oldest agrarian educatio ...

) in 1906. During this time he became known for carrying a pet lizard in his pocket wherever he went. He graduated from the Petrovka in 1910 with a dissertation on snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class G ...

s as pests

PESTS was an anonymous American activist group formed in 1986 to critique racism, tokenism, and exclusion in the art world. PESTS produced newsletters, posters, and other print material highlighting examples of discrimination in gallery represent ...

. From 1911 to 1912, he worked at the Bureau for Applied Botany and at the Bureau of Mycology

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungi, including their genetic and biochemical properties, their taxonomy and their use to humans, including as a source for tinder, traditional medicine, food, and entheogen ...

and Phytopathology. From 1913 to 1914 he travelled in Europe and studied plant immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

, in collaboration with the British biologist William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

, who helped establish the science of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

.

From 1917 to 1920, he was a professor at the Faculty of Agronomy, University of Saratov. His son Oleg (with his first wife Yekaterina Sakharova) was born in 1918.

From 1924 to 1935 he was the director of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences at Leningrad. Impressed with the work of Canadian phytopathologist Margaret Newton on wheat stem rust

Stem rust, also known as cereal rust, black rust, red rust or red dust, is caused by the fungus ''Puccinia graminis'', which causes significant disease in cereal crops. Crop species that are affected by the disease include bread wheat, durum w ...

, in 1930 he attempted to hire her to work at the institute, offering a good salary and perks such as a camel caravan for her travel. She declined, but visited the institute in 1933 for three months to train 50 students in her research.

Vavilov's first marriage ended in divorce in 1926, after which he married geneticist Elena Ivanovna Barulina, a specialist on lentil

The lentil (''Lens culinaris'' or ''Lens esculenta'') is an edible legume. It is an annual plant known for its lens-shaped seeds. It is about tall, and the seeds grow in pods, usually with two seeds in each. As a food crop, the largest pro ...

s and assistant head of the institute's seed collection. Their son Yuri was born in 1928.

Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, he created the world's largest collection of plant seeds. Vavilov also formulated the law of homologous series in variation. He was a member of the USSR Central Executive Committee, President of All-Union Geographical Society and a recipient of the Lenin Prize.

In 1932, during the sixth congress, Vavilov proposed holding the seventh International Congress of Genetics in the USSR. After some initial resistance by the organizing committee, in 1935 it agreed to hold the seventh congress in Moscow in 1937. The Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences decided to support the idea and asked the Communist Party for its approval, which it gave on 31 July 1935. Vavilov was elected chairman of the International Congress of Genetics. However, on 14 November 1936 the Politburo decided to cancel the congress. The seventh International Congress of Genetics was postponed until 1939 and took place in Edinburgh instead. The Politburo had decided to forbid Vavilov from travelling abroad and during the Congress's opening ceremony an empty chair was placed on the stage as a symbolic reminder of Vavilov's involuntary absence.

Vavilov encountered the young

Vavilov encountered the young Trofim Lysenko

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (russian: Трофим Денисович Лысенко, uk, Трохи́м Дени́сович Лисе́нко, ; 20 November 1976) was a Soviet agronomist and pseudo-scientist.''An ill-educated agronomist with hu ...

and at first he encouraged Lysenko's work. However, Vavilov changed his mind and became an outspoken critic of Lysenko, because Lysenko did not believe in genetics and Vavilov feared that Lysenko's ideas could be disastrous for Soviet agriculture. Vavilov publicly criticized Lysenko both at home and while on foreign trips. However, Stalin believed in Lysenko's theories, and as a result, so did the rest of the Soviet government. The Soviet authorities suspected that Vavilov was trying to sabotage Soviet agriculture with bad science, and their suspicions were aggravated by his associations with other scientists who had been convicted of espionage, some of whom falsely implicated Vavilov in counter-revolutionary activities. As a result, Vavilov was arrested on 6 August 1940, while on an expedition to Ukraine. He was sentenced to death in July 1941. In 1942 his sentence was commuted to twenty years imprisonment. In 1943, he died in prison as a result of the harsh conditions. The prison's medical documentation indicates that he had been admitted into the prison hospital a few days prior to his death and mention the diagnoses of lung inflammation, dystrophy

Dystrophy is the degeneration of tissue, due to disease or malnutrition, most likely due to heredity.

Types

* Muscular dystrophy

** Duchenne muscular dystrophy

** Becker's muscular dystrophy

** Myotonic dystrophy

* Reflex neurovascular dyst ...

and edema as well as general weakness as a complaint, but as for the immediate cause of death, the death certificate only mentions 'decline of cardiac activity'.(in Russian) Some authors assert that the actual cause of death was starvation. The Pavlovsk Experimental Station, Leningrad seedbank was preserved and protected through the 28-month long Siege of Leningrad. While the Soviets had ordered the evacuation of art from the

Hermitage Museum

The State Hermitage Museum ( rus, Государственный Эрмитаж, r=Gosudarstvennyj Ermitaž, p=ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj ɪrmʲɪˈtaʂ, links=no) is a museum of art and culture in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It is the largest ...

, they had not evacuated the 250,000 samples of seeds, roots, and fruits stored in what was then the world's largest seedbank. A group of scientists at the Vavilov Institute boxed up a cross section of seeds, moved them to the basement, and took shifts protecting them. Those guarding the seedbank refused to eat its contents, even though by the end of the siege in the spring of 1944, a number of them had died of starvation.

In 1943, parts of Vavilov's collection, samples stored within the territories occupied by the German armies, mainly in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, were seized by a German unit headed by Heinz Brücher

Heinz Brücher (14 January 1915, Darmstadt, Grand Duchy of Hesse – 17 December 1991, Mendoza Province, Argentina) was a botanist and plant breeder who served as a member of the special science unit in the SS Ahnenerbe in Nazi Germany. He was ...

. Many of the samples were transferred to the Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe d ...

(SS) Institute for Plant Genetics, which had been established at near Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popul ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

.

The Royal Society of Edinburgh mentions Vavilov in the list of its former fellows, indicating that he died in a Soviet workcamp in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

on 26 January 1943. However, he actually died in a Soviet prison in Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901,36 ...

.

Vavilov was an atheist.Pringle, Peter (2008). The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin's Persecution of One of the Great Scientists of the Twentieth Century. Simon and Schuster. p. 137. . "Despite his strict upbringing in the Orthodox Church, Vavilov had been an atheist from an early age. If he worshipped anything, it was science."

Posthumous rehabilitation

In 1955, Vavilov's life sentence was pardoned at a hearing of theMilitary Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union

The Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union ( Russian: Военная коллегия Верховного суда СССР, ''Voennaya kollegiya Verkhovnogo suda SSSR'') was created in 1924 by the Supreme Court of the Sov ...

, undertaken as part of a de-Stalinization effort to review Stalin-era death sentences. By the 1960s his reputation was publicly rehabilitated and he began to be hailed as a hero of Soviet science

Science and technology in the Soviet Union served as an important part of national politics, practices, and identity. From the time of Lenin until the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s, both science and technology were intimately linked ...

.

Conspiracy allegations

The warrant for Vavilov's arrest was issued by 1st Lt. Vladimir Ruzin of the NKVD, with the approval of Mikhail Pankratyev, the Deputy Prosecutor of the USSR, andLavrenty Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

. Ruzin accused Vavilov of foreign espionage and sabotage.

Legacy

Namesakes

Today a street in downtown Saratov bears Vavilov's name. Vavilov's monument in Saratov near the end of the Vavilov street was unveiled in 1997. The square near the monument is a common place for opposition rallies. Another monument to him is located near the entrance to the Resurrection cemetery in Saratov, where Vavilov is buried. TheUSSR Academy of Sciences

The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union was the highest scientific institution of the Soviet Union from 1925 to 1991, uniting the country's leading scientists, subordinated directly to the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (until 1946 ...

established the Vavilov Award (1965) and the Vavilov Medal (1968).

Today, the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry in St. Petersburg still maintains one of the world's largest collections of plant genetic material. The Institute began as the Bureau of Applied Botany in 1894, and was reorganized in 1924 into the All-Union Research Institute of Applied Botany and New Crops, and in 1930 into the Research Institute of Plant Industry. Vavilov was the head of the institute from 1921 to 1940. In 1968 the institute was renamed after Vavilov in time for its 75th anniversary.

A minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''mino ...

, 2862 Vavilov, discovered in 1977 by Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh is named after him and his brother Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov

Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Вави́лов ( – January 25, 1951) was a Soviet physicist, the President of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union from July 1945 until his death. His elder brothe ...

. The crater ''Vavilov Vavilov (russian: Вави́лов) is a Russian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrey Petrovich Vavilov (b. 1961), Russian politician and businessman

* Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943), Russian geneticist

* Sergey Ivanovich Vavi ...

'' on the far side of the Moon

The far side of the Moon is the lunar hemisphere that always faces away from Earth, opposite to the near side, because of synchronous rotation in the Moon's orbit. Compared to the near side, the far side's terrain is rugged, with a multitu ...

is also named after him and his brother.

Media

The story of the researchers at the Vavilov Institute during the Siege of Leningrad was fictionalized by novelistElise Blackwell

Elise Blackwell is an American novelist and writer. She is the author of five novels, as well as numerous short stories and essays. Her books have been translated into five languages, adapted for the stage, and served as the inspiration for the s ...

in her 2003 novel ''Hunger''. That novel was the inspiration for the Decemberists

The Decemberists are an American indie rock band from Portland, Oregon. The band consists of Colin Meloy ( lead vocals, guitar, principal songwriter), Chris Funk (guitar, multi-instrumentalist), Jenny Conlee (piano, keyboards, accordion), Nate ...

' song "When The War Came" in the 2006 album '' The Crane Wife'', which also depicts the Institute during the siege and mentions Vavilov by name.

In 1987, the Shevchenko National Prize

Shevchenko National Prize ( uk, Націона́льна пре́мія Украї́ни і́мені Тараса́ Шевче́нка; also ''Shevchenko Award'') is the highest state prize of Ukraine for works of culture and arts awarded since ...

was awarded to Anatoliy Borsyuk (film director), Serhiy Dyachenko

Spouses Maryna Yuryivna Dyachenko (born 23 January 1968) and Serhiy Serhiyovych Dyachenko (14 April 1945 – 5 May 2022) (Marina Yuryevna Dyachenko (Shirshova) and Sergey Sergeyevich Dyachenko) (rus. Марина и Сергей Дяченко, ...

(script writer), and Oleksandr Frolov (camera) for the film ''Star of Vavilov'' (Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

: "Звезда Вавилова") about Vavilov's work.

In 1990, a six part documentary entitled Nikolai Vavilov

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov ( rus, Никола́й Ива́нович Вави́лов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ vɐˈvʲiləf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Ivanovich_Vavilov.ogg; – 26 January 1943) was a Russian and Soviet agronomist, botanist ...

(Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

: Николай Вавилов), was created as a joint production of the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

.

Season 1, Episode 4 of the 2020 science documentary series, Cosmos: Possible Worlds starring Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson ( or ; born October 5, 1958) is an American astrophysicist, author, and science communicator. Tyson studied at Harvard University, the University of Texas at Austin, and Columbia University. From 1991 to 1994, he was a p ...

and based on the original series by Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ext ...

, was titled "Vavilov" and detailed his life.

Works

* Земледельческий Афганистан. (1929) (''Agricultural

Земледельческий Афганистан. (1929) (''Agricultural Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

'')

*Селекция как наука. (1934) (''Breeding as science'')

*Закон гомологических рядов в наследственной изменчивости. (1935) (''The law of homology series in genetical mutability'')

*Учение о происхождении культурных растений после Дарвина. (1940) (''The theory of origins of cultivated plants after Darwin'')

*Географическая локализация генов пшениц на земном шаре. (1929) (''The Geographical Localization of Wheat Genes on the Earth'')

Works in English

*''The Origin, Variation, Immunity and Breeding of Cultivated Plants'' (translated by K. Starr Chester). 1951. Chronica Botanica 13:1–366link

*''Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants'' (translated by

Doris Löve

Doris Benta Maria Löve, ''née'' Wahlén (born 2 January 1918 in Kristianstad – deceased 25 February 2000 in San Jose, California) was a Swedish systematic botanist, particularly active in the Arctic.

Biography

Doris Löve was born in Kris ...

). 1987. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

*Five Continents

' (translated by

Doris Löve

Doris Benta Maria Löve, ''née'' Wahlén (born 2 January 1918 in Kristianstad – deceased 25 February 2000 in San Jose, California) was a Swedish systematic botanist, particularly active in the Arctic.

Biography

Doris Löve was born in Kris ...

). 1997. IPGRI, Rome; VIR, St. Petersburg.

See also

*VASKhNIL

VASKhNIL (), the acronym for the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences or the V.I. Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences (), was the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. w ...

(the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences of the Soviet Union)

*All-Russian Institute of Plant Industry

The Institute of Plant Industry, Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry or All-Russian Research Institute of Plant Industry (in russian: Всероссийский институт растениеводства им. Н. И. Вавилова), as ...

*Vavilovian mimicry

In plant biology, Vavilovian mimicry (also crop mimicry or weed mimicry) is a form of mimicry in plants where a weed evolves to share one or more characteristics with a domesticated plant through generations of artificial selection. It is name ...

*Vavilov Center

A center of origin is a geographical area where a group of organisms, either domesticated or wild, first developed its distinctive properties. They are also considered centers of diversity. Centers of origin were first identified in 1924 by Ni ...

*Lysenkoism

Lysenkoism (russian: Лысенковщина, Lysenkovshchina, ; uk, лисенківщина, lysenkivščyna, ) was a political campaign led by Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko against genetics and science-based agriculture in the mid-20th ce ...

References

Further reading

* Where Our Food Comes From: Retracing Nikolay Vavilov's Quest to End Famine byGary Paul Nabhan

Gary Paul Nabhan (born 1952) is an agricultural ecologist, Ethnobotanist, Ecumenical Franciscan Brother, and author whose work has focused primarily on the plants and cultures of the desert Southwest. He is considered a pioneer in the local food ...

2008

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Kurlovich, B.S. WHAT IS A SPECIES? ''https://sites.google.com/site/biodiversityoflupins/15-objective-regularities-in-the-variability-of-chatacters/what-is-a-species''

* Reznik, S. and Y. Vavilov 1997 "The Russian Scientist Nikolay Vavilov" (preface to English translation of:) Vavilov, N. I. ''Five Continents''. IPGRI: Rome, Italy.

* Cohen, Barry Mendel 1980 ''Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov: His Life and Work''. Ph.D.: University of Texas at Austin.

*

*''Vavilov and his Institute. A history of the world collection of plant genetic resources in Russia'', Loskutov, Igor G. 1999. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy.

External links

Vavilov, Centers of Origin, Spread of Crops

* ttps://www.marxists.org/subject/science/essays/speeches.htm#vavilov Speech at the 1939 Conference on Genetics and Selectionbr>Theoretical base of our researches

{{DEFAULTSORT:Vavilov, Nikolai Ivanovich 1887 births 1943 deaths Scientists from Moscow People from Moskovsky Uyezd All-Russian Central Executive Committee members Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members Russian atheists Russian agronomists Soviet botanists Soviet agronomists 20th-century Russian botanists Botanists with author abbreviations Russian geneticists Soviet geneticists Russian geographers Soviet geographers Russian explorers 20th-century geographers Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Members of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Academicians of the VASKhNIL Foreign Members of the Royal Society Deaths by starvation Soviet people who died in prison custody Prisoners who died in Soviet detention Soviet rehabilitations